Recent articles about radiation safety from The New York Times keep reminding me of something I learned my first year of residency: radiation oncology is one of the most opaque specialties in medicine. And it’s hurting our ability to help our patients.

During one of my first rotations at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, I spent time following a renowned medical oncologist around in clinic. One of his patients needed radiation therapy. “Just buzz him,” he said. Further discussion made it clear: he had no sense of how the radiation was done, and he had not seen a linear accelerator in two decades in oncology.

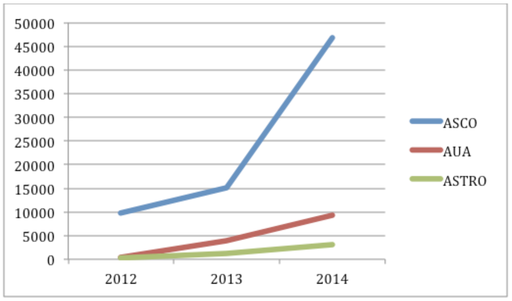

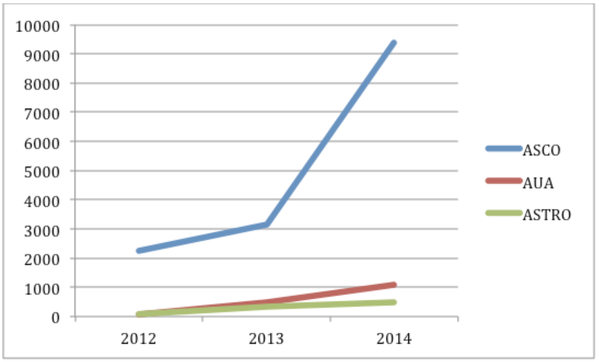

In the decade since that conversation, I’ve continually been impressed by the degree of fear and misinformation surrounding radiation oncology. As a volunteer with ASTRO, I believe we need to focus more effort on effectively communicating what we do. Unless we dedicate ourselves to telling our stories, The New York Times and others will do it for us.

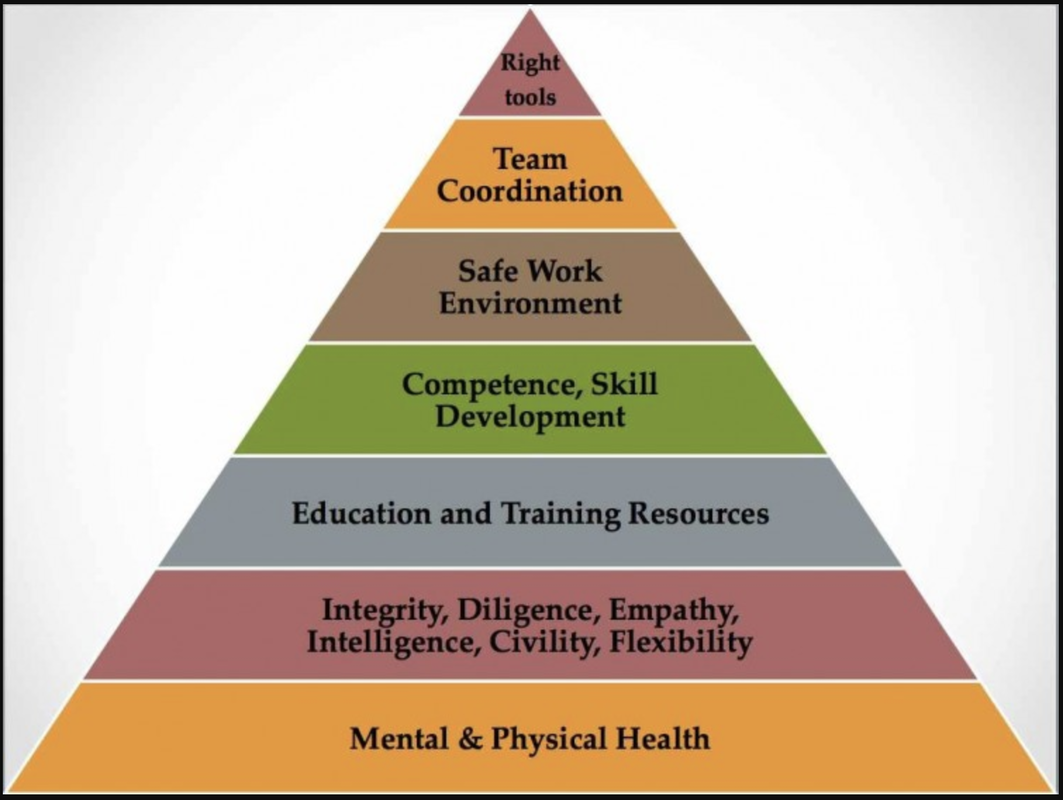

To some extent, radiation oncology is a victim of its own successes. Technical and scientific advances have been exciting and beneficial to our patients. Often, the overt emphasis in training is on technology, expertise and specialization. Interpersonal skills are valued but not often cultivated or taught. Unless we want to be technicians, we must use the humanistic aspects of our training more rigorously.

Despite the rigor we instill into our work, ultimately medicine is a social science. Doctor means teacher in Latin. Whether it’s a breast cancer patient afraid that radiation will make her lose her hair or the congressional aide who thinks you are a radiologist, you can share your knowledge and stories to help educate them.

Better communication can also help inform the nurses, therapists, dosimetrists, physicists, administrative assistants and other health professionals we depend upon so that we provide better, safer treatment. Communicating is a learned skill, so we need to work at it. But that’s why it’s called medical practice, after all.

If we hone our skills in storytelling and put a human face on the field, radiation oncology will be better able to provide a clear, cogent narrative on many important issues:

But sharing must flow both ways. Listening to the stories of our patients, colleagues, and critics can help us heal more effectively and provide new opportunities to improve cancer care. Whether it’s in an exam room or a chat room, at an academic conference or a tweetup, we are in an ideal position to improve the health and quality of digital life. Social media are no panacea, but if we don’t learn how to communicate effectively both in person and online, our ability to meaningfully care and advocate for our patients will be diminished. When we do learn how to share, the story is more likely to have a happy ending.

Matthew Katz, M.D. is a member of the Advisory Board for the Mayo Clinic Center for Social Media. This article is adapted from his original post at ASTROnews.

Originally posted on Mayo Clinic Center for Social Media, May 11, 2011

During one of my first rotations at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, I spent time following a renowned medical oncologist around in clinic. One of his patients needed radiation therapy. “Just buzz him,” he said. Further discussion made it clear: he had no sense of how the radiation was done, and he had not seen a linear accelerator in two decades in oncology.

In the decade since that conversation, I’ve continually been impressed by the degree of fear and misinformation surrounding radiation oncology. As a volunteer with ASTRO, I believe we need to focus more effort on effectively communicating what we do. Unless we dedicate ourselves to telling our stories, The New York Times and others will do it for us.

To some extent, radiation oncology is a victim of its own successes. Technical and scientific advances have been exciting and beneficial to our patients. Often, the overt emphasis in training is on technology, expertise and specialization. Interpersonal skills are valued but not often cultivated or taught. Unless we want to be technicians, we must use the humanistic aspects of our training more rigorously.

Despite the rigor we instill into our work, ultimately medicine is a social science. Doctor means teacher in Latin. Whether it’s a breast cancer patient afraid that radiation will make her lose her hair or the congressional aide who thinks you are a radiologist, you can share your knowledge and stories to help educate them.

Better communication can also help inform the nurses, therapists, dosimetrists, physicists, administrative assistants and other health professionals we depend upon so that we provide better, safer treatment. Communicating is a learned skill, so we need to work at it. But that’s why it’s called medical practice, after all.

If we hone our skills in storytelling and put a human face on the field, radiation oncology will be better able to provide a clear, cogent narrative on many important issues:

- How radiation can cure and alleviate suffering;

- Our commitment to our patients;

- How we work together to provide radiation treatment safely and effectively;

- Why self-referral threatens the quality and cost of cancer care.

- The need to invest in cancer research.

But sharing must flow both ways. Listening to the stories of our patients, colleagues, and critics can help us heal more effectively and provide new opportunities to improve cancer care. Whether it’s in an exam room or a chat room, at an academic conference or a tweetup, we are in an ideal position to improve the health and quality of digital life. Social media are no panacea, but if we don’t learn how to communicate effectively both in person and online, our ability to meaningfully care and advocate for our patients will be diminished. When we do learn how to share, the story is more likely to have a happy ending.

Matthew Katz, M.D. is a member of the Advisory Board for the Mayo Clinic Center for Social Media. This article is adapted from his original post at ASTROnews.

Originally posted on Mayo Clinic Center for Social Media, May 11, 2011

RSS Feed

RSS Feed